Since January 2016, discreet campaigns involving malware called Trojan. Odinaff have targeted a number of financial organizations worldwide. These attacks appear to be extremely focused on organizations operating in the banking, securities, trading, and payroll sectors. Organizations who provide support services to these industries are also of interest.

Odinaff is typically deployed in the first stage of an attack, to gain a foothold onto the network, providing a persistent presence and the ability to install additional tools onto the target network. These additional tools bear the hallmarks of a sophisticated attacker which has plagued the financial industry since at least 2013–Carbanak. This new wave of attacks has also used some infrastructure that has previously been used in Carbanak campaigns.

These attacks require a large amount of hands on involvement, with methodical deployment of a range of lightweight back doors and purpose built tools onto computers of specific interest. There appears to be a heavy investment in the coordination, development, deployment, and operation of these tools during the attacks. Custom malware tools, purpose built for stealthy communications (Backdoor.Batel), network discovery, credential stealing, and monitoring of employee activity are deployed.

Although difficult to perform, these kinds of attacks on banks can be highly lucrative. Estimates of total losses to Carbanak-linked attacks range from tens of millions to hundreds of millions of dollars.

Global threat

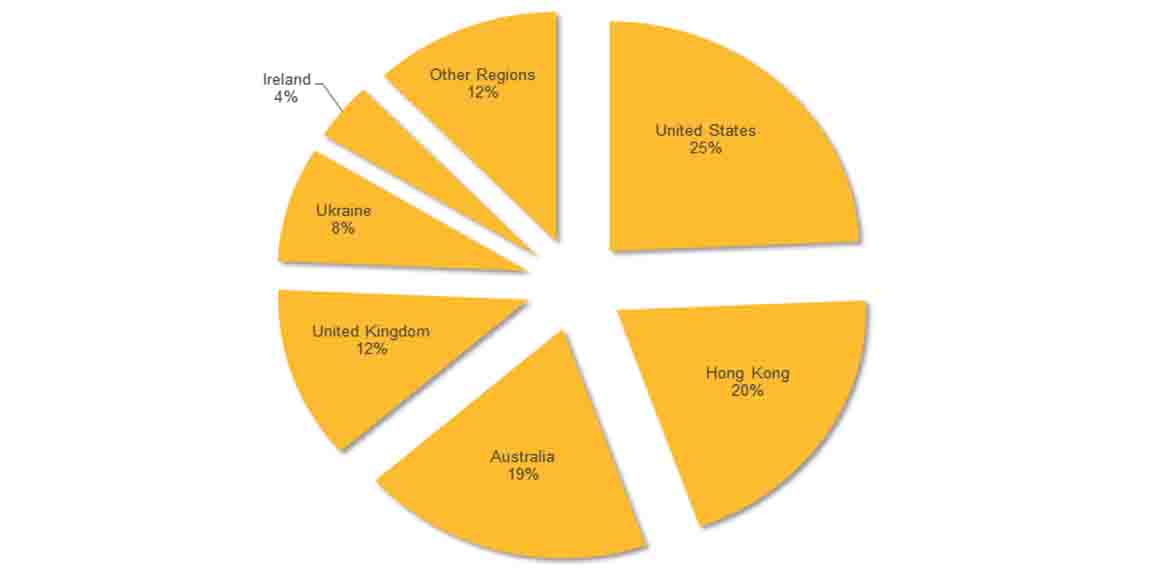

Attacks involving Odinaff appear to have begun in January 2016. The attacks have hit a wide range of regions, with the US the most frequently targeted. It was followed by Hong Kong, Australia, the UK and Ukraine.

Figure 1. Odinaff attacks by region

Most Odinaff attacks were against financial targets. In attacks where the nature of the victim’s business was known, financial was by far the most frequently hit sector, accounting for 34 percent of attacks. There were a small number of attacks against organizations in the securities, legal, healthcare, government and government services targets; however, it is unclear whether all of these were financially motivated.

Around 60 percent of attacks were against targets whose business sector was unknown, but in many cases these were against computers running financial software applications, meaning the attack was likely financially motivated.

Figure 2. Odinaff attacks by sector

Initial point of attack

The Odinaff attackers’ use a variety of methods to break into the networks of targeted organizations. One of the most common methods of attack is through lure documents containing a malicious macro. If the recipient opts to enable macros, the macro will install the Odinaff Trojan on their computer.

Figure 3. Lure document containing instructions on how to enable Word macros.

Another attack involves the use of password protected RAR archives, in order to lure the victims into installing Odinaff on their computers. Although Symantec has not seen how these malicious documents or links are distributed, we believe spear-phishing emails are the most likely method.

Trojan.Odinaff has also been seen to be distributed through botnets, where the Trojan is pushed out to computers already infected with other malware, such as Andromeda (Downloader.Dromedan) and Snifula (Trojan.Snifula). In the case of Andromeda, this was bundled as a Trojanized installer for AmmyyAdmin, a legitimate remote administration tool. The Trojanized installer was downloaded from the official website, which has been targeted repeatedly in recent times to spread a number of different malware families.

Malware toolkit

Odinaff is a relatively lightweight back door Trojan which connects to a remote host and looks for commands every five minutes. Odinaff has two key functions: it can download RC4 encrypted files and execute them and it can also issue shell commands, which are written to a batch file and then executed.

Given the specialist nature of these attacks, a large amount of manual intervention is required. The Odinaff group carefully manages its attacks, maintaining a low profile on an organization’s network, downloading and installing new tools only when needed.

Trojan.Odinaff is used to perform the initial compromise, while other tools are deployed to complete the attack. A second piece of malware known as Batle (Backdoor.Batel) is used on computers of interest to the attackers. It is capable of running payloads solely in memory, meaning the malware can maintain a stealthy presence on infected computers.

The attackers make extensive use of a range of lightweight hacking tools and legitimate software tools to traverse the network and identify key computers. These include:

• Mimikatz, an open source password recovery tool

• PsExec, a process execution tool from SysInternals

• Netscan, a network scanning tool

• Ammyy Admin (Remacc.Ammyy) and Remote Manipulator System variants (Backdoor.Gussdoor)

• Runas, a tool for running processes as another user.

• PowerShell

The group also appears to have developed malware designed to compromise specific computers. The build times for these tools were very close to the time of deployment. Among them were components capable of taking screenshot images at intervals of between five and 30 seconds.

Evidence of attacks on SWIFT users

Symantec has found evidence that the Odinaff group has mounted attacks on SWIFT users, using malware to hide customers’ own records of SWIFT messages relating to fraudulent transactions. The tools used are designed to monitor customers’ local message logs for keywords relating to certain transactions. They will then move these logs out of customers’ local SWIFT software environment. We have no indication that SWIFT network was itself compromised.

These “suppressor” components are tiny executables written in C, which monitor certain folders for files that contain specific text strings. Among the strings seen by Symantec are references to dates and specific International Bank Account Numbers (IBANs).

The folder structure in these systems seem to be largely user defined and proprietary, meaning each executable appears to be clearly tailored to for a target system.

One of the files found along with the suppressor was a small disk wiper which overwrites the first 512 bytes of the hard drive. This area contains the Master Boot Record (MBR) which is required for the drive to be accessible without special tools. We believe this tool is used to cover the attackers’ tracks when they abandon the system and/or to thwart investigations.

These Odinaff attacks are an example of another group believed to be involved in this kind of activity, following the Bangladesh central bank heist linked to the Lazarus group. There are no apparent links between Odinaff’s attacks and the attacks on banks’ SWIFT environments attributed to Lazarus and the SWIFT-related malware used by the Odinaff group bears no resemblance to Trojan.Banswift, the malware used in the Lazarus-linked attacks.

Possible links to Carbanak

The attacks involving Odinaff share some links to the Carbanak group, whose activities became public in late 2014. Carbanak also specializes in high value attacks against financial institutions and has been implicated in a string of attacks against banks in addition to point of sale (PoS) intrusions.

Aside from the similar modus operandi, there are a number of other links between Carbanak and Odinaff:

• There are three command and control (C&C) IP addresses which have been connected to previously reported Carbanak campaigns.

• One IP address used by Odinaff was mentioned in connection with the Oracle MICROS breach, which was attributed to the Carbanak group.

• Backdoor.Batel has been involved in multiple incidents involving Carbanak.

Since Carbanak’s main Trojan, Anunak (Trojan.Carberp.B and Trojan.Carberp.D) was never observed in campaigns involving Odinaff, we firmly believe the group uses a number of discreet distribution channels to compromise financial organizations.

While it is possible that Odinaff is part of the wider organization, the infrastructure crossover is atypical, meaning it could also be a similar or cooperating group.

Banks increasingly in the crosshairs

The discovery of Odinaff indicates that banks are at a growing risk of attack. Over the past number of years, cybercriminals have begun to display a deep understanding of the internal financial systems used by banks. They have learned that banks employ a diverse range of systems and have invested time in finding out how they work and how employees operate them. When coupled with the high level of technical expertise available to some groups, these groups now pose a significant threat to any organization they target.